- Why Paint?

Judy Ledgerwood, Composition in Apricot and Violet, 1990.

Judy Ledgerwood, Composition in Apricot and Violet, 1990.

Jim Lutes, Road Condition, 1992.

Kay Rosen, Six, 1986.

Jim Lutes, Wizened, 1992.

Kevin Wolff, Curled Finger, 1992.

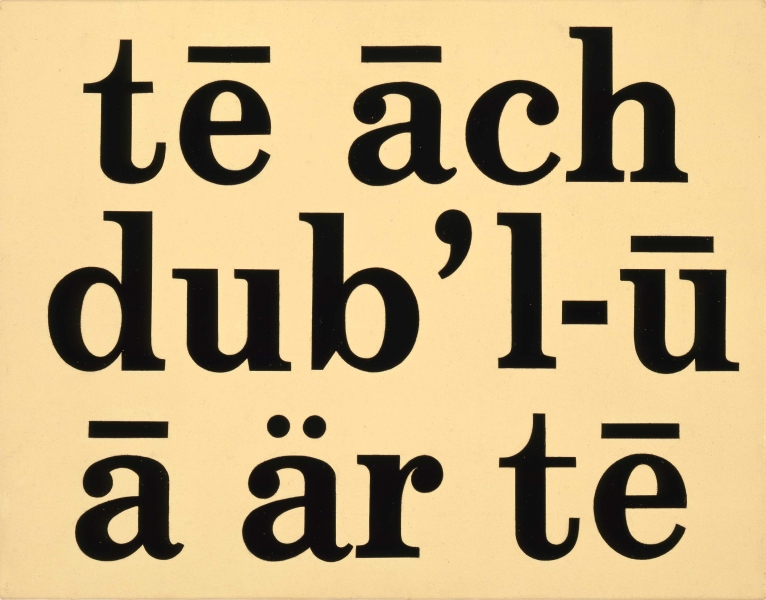

Kay Rosen, t-h-w-a-r-t, 1989.

Why Paint?, Installation View, 1992.

Why Paint?, Installation View, 1992.

Why Paint?, Installation View, 1992.

Why Paint?, Installation View, 1992.

Why Paint?, Installation View, 1992.

Judy Ledgerwood, Composition in Apricot and Violet, 1990.

The four artists included in this exhibition provide four varied and impressive responses to the rhetorical question “Why paint?”, offering proof that painting indeed continues as a viable form of art—and communication—as we settle into the 1990s.

During the last 25 years many artists, art historians and critics have declared that painting is over with, finished, dead in relation to our burgeoning “Information Age.” From the frescoed walls of 14th century Italian estates to the pictorial intervention of photography; from Courbet and Manet to the “rectangularly-shaped canvases stretched over wooden supports and stained with such and such colors, using such and such forms, giving such and such a visual experience, etc.” of Joseph Kosuth, painting would seem to have lost its relevance in an era of computers, videotape, and the global media.

However, those traits that supposedly have contributed to paintings’s communicative demise are in fact responsible for its continued artistic appeal: material sensuality, figurative depiction, hand labor-intensiveness, and intellectual, spiritual and emotional expression. Painting has not suffered in light of recent technology but seems to have flourished because of it.

The primary difference in recent years seems to be the newly asserted cleft of responsibility between the fact-based, technological representations of the media, and the more personally expressive or reflective representations found in painting. Now, more than any time in recent years, painting exists as a thing in itself, as Painting: free from having to validate its place in human drama, free from the media’s “burden of proof,” free to assert its sensuous and hand-made traits in various forms of portraiture, abstraction or language. As evidence of artist’s concerns, passions, observations and mental processes, painting provides degrees of subjectivity and sensual pleasure that no other imaging technology can match.